[Forgive me another bout of grave-robbing. I had written a version of what follows for the 8/9 issue of PW

, in honor of an Alejandro Jodorowsky night put on by the estimable underground filmmaker Andrew Repasky McElhinney that paired 1973’s The Holy Mountain

with 1990’s The Rainbow Thief

. It wound up running long, and I had to cut it down to meet my not terribly lengthy word quota. But then a whirlwind of activity hit the film section and my editor was forced to edit it down further still, reducing it to a lengthy introduction and then plot summary. I know you’ve figured the rest of the story out by now: I’ve taken what I had originally written, beefed it up, and found some pics to give it a vaguely professional sheen. Bon appetit, beetches!]

Cult filmmakers don’t get much more cult than Alejandro Jodorowsky, the Chilean-born rennaissance man who’s so under the radar, most of his cinematic output has been nearly impossible to see. You can thank John Lennon for that. Having declared

El Topo - Jodorowsky’s bloody, ponderous, surrealist western and the first serious midnight movie sensation - his favorite film, Lennon advised infamous Sam Cooke/Rolling Stones business manager Allen Klein to snatch up the rights, as well as those of what would become his follow-up, 1973’s

The Holy Mountain. Klein then held the two in limbo, keeping them out of theaters and off shelves. (The curious have long subsisted on more-than-passable bootlegs, some of which can be found at Philly's smattering of TLAs.) Jodorowsky and Klein made peace in 2004, and well-belated DVD are reportedly in the works. (Who knows when they’ll arrive is, to put it mildly, another matter.) But the damage seems mostly done, an entire generation having grown up without easy access to his work and the director himself not being able to use them to raise money for more. Though it’d be hard to sweat off his aborted attempt to make an all-star version of

Dune in the 1970s -- Orson Welles as the Baron, Salvador Dali as the Emperor, Mick Jagger as Feyd Rautha and H.R. Giger on design duty -- at least its chances for existence are well and gone. Not so with his on-again-off-again attempts to make an

El Topo sequel, which at one point co-starred Marilyn Manson, which currently appears to be in the “off” position.

Funded entirely out of John and Yoko’s pockets,

The Holy Mountain is a classic follow-up to a success: bigger, more ambitious, more philosophically pretentious and at least twice as gory as the film that spawned it. But an elephantine scale (and cinemascope) actually proves a better fit for the director than the ramshackleness of

El Topo, if only because Jodorowsky has the kind of overwrought, devil-may-care sensibility that’s best aided by spectacle and its promise of a new, impossible-to-foresee sensation on the minute. Jodorowsky delivers. Indeed, on some level,

Mountain ranks up with

Kane and

8 1/2 in its portrait of a filmmaker as kid in a toy shop, and as a pure riot of set design insanity, it sits alongside Donen at his most ostentatious.

Again melding Buñuel with Fellini, Jodorowsky spins the tale of a Christ-resembling thief who joins up with a white-haired alchemist (Jodorowsky himself) and seven of the planet’s most flamboyantly rich subjects to shed their material wealth and scale said mountain, at which point they’ll achieve immortality. As with

El Topo,

Mountain is neatly divided in three sections, constituting a philosophical journey to a hoped-for state of grace. Unlike

El Topo,

Mountain has no clear lead character, making it harder for we, the audience, to (attempt to) tag along.

But it also makes it easier to focus on the scattershot nature of his ideas, and for the better. The first section, with our long-haired klepto getting mistaken and exploited for his resemblance to J.C., may in fact contain more sacrilegious images than a Buñuel retro. (

Un Chien Andalou’t ant-hand gets directly referenced at one point.) But he proves increasingly incidental to the plot, starting with the section that introduces us to the seven greats one-by-one in short, impossibly dense bursts. Within each one, Jodorowsky seems to be dumping his grievances with society, albeit in strange-comic ways: one guy runs a factory that makes, among other things, gadgets that make corpses feign kisses, so they can recipricate at viewings. Another, who works in the art world, has constructed a giant orgasm machine that, when correctly prodded, births a baby orgasm machine. Then again, the film’s density can prove exhausting: by the third, even less focused section, even a man holding up tiny tiger heads up to his nipples that then spew milk in slow-mo can’t get much of a rise.

As usual, the filmmaker plays fast and loose with the ideas. But also as usual, cohesion’s not really the point. Jodorowsky wants to hit the viewer with sensations in such a way that ideas have the same visceral impact as violence or imagery. That said, they’re blunt and sometimes questionable ideas. Given the well-tipped ratio of nudity from women and men (and Jodorowsky claims to have slept with all his actresses), what to make that both of the chosen ones’ lone femmes deal in guns? And what’s with the total lack of apparent outrage when the fabulously wealthy septet burn their scores of cash, rather than give it to Mexico’s impoverished? (It’s infinitely more appaling than the similar scene in Michael Haneke’s

The Seventh Continent, where the characters were clearly losing their tether.) Jodorowsky is at least as interested in making satirical jabs as he is being mystical and shit -- maybe even moreso -- but even they feel thrown-off and slapdash, less a clearly thought-through vision of the world than a hyper-pixilated version of same.

But while I’ve never seriously bought into Jodorowsky’s ideas -- here’s a dude who invented a kind of New Age therapy called “psychomagic” -- I have developed a, shall we say, zen-like detachment from it, or more accurately, a willingness to read it as entertaining in its nuttiness. Far more satisfyingly than

El Topo, the film feels like an all-you-can-eat buffet, where you can choose what philosphies or satirical jabs you like and politely decline the rest. It’s not even clear how much of it he agrees with, and then, which ones. But inclusiveness may be part of his plan, and besides, it’s dizzying -- especially during the first two, more patently satirical sections -- to follow him from place to place, target to target. (You won’t soon forget the moment where our pseudo-J.C. awakens screaming in a warehouse full of models of himself, let alone the poo-to-gold machine.) It's undeniably silly, but as soon as it was over, I couldn't wait to watch it again.

After

Mountain never received a stateside theatrical release, Jodorowsky all but disappeared, surfacing only thrice in the interim. Made just after the return-to-form that was

Santa Sangre, 1990’s

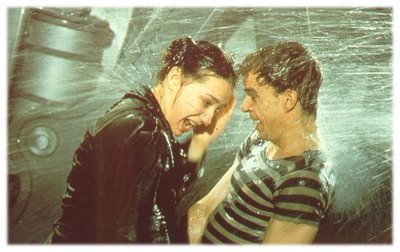

The Rainbow Thief finds a de-fanged Jodorowsky infiltrating the world of middlebrow international cinema, with Omar Shariff as a bum playing butler to Peter O’Toole’s sewer-dwelling heir - a potentially queasy premise to be sure. To his credit, he fails miserably, damaging the film with fuzzy plotting (test audiences said they couldn’t even find the story) and rampant weirdness, much of it during the opening where Christopher Lee plays a dalmation-obsessed billionaire who serves giant bones to his guests. Still, better a failed attempt to play straight than a successful calcification, best epitomized by the way the threatened ham-off between Shariff and O’Toole never even starts, the latter ceding to the aging Mediterranean dreamboat without so much as a glove-slap. Shariff, unpredictably, delivers some unsightly mugging, but there’s a dark side to his turn, and a couple times where he could turn murderous. The ostenatious rainfall that eats up most of the final half hour is techinically impressive, but it’s sad to think that, should the upcoming DVDs not result in the handing-over of a budget to Jodorowsky’s whims -- or worse, his game is now gone -- this would be where his oeuvre stops.

So, I went and neglected to post my Weekly crap last week. Sorry, scant readers. Basically, Philly's going through a French period: here are reviews of André Téchiné's Changing Times, Géla Babluani's miserablist high-concept 13 (Tzameti) (at the bottom, though don't skip Sean Burns' evisceration of the suffocatingly retro-smug-sounding The Quiet), and Emmanuel Carrère's La Moustache (second one down), which actually finds a fresh spin on madness, as well as fractured relationships. (Also, if there's any doubt, the picture to your right is not a snapshot of Moustache star Vincent Lindon, who looks more like a Gallic Huey Lewis.) Also, last week's Rep and this week's Rep.

So, I went and neglected to post my Weekly crap last week. Sorry, scant readers. Basically, Philly's going through a French period: here are reviews of André Téchiné's Changing Times, Géla Babluani's miserablist high-concept 13 (Tzameti) (at the bottom, though don't skip Sean Burns' evisceration of the suffocatingly retro-smug-sounding The Quiet), and Emmanuel Carrère's La Moustache (second one down), which actually finds a fresh spin on madness, as well as fractured relationships. (Also, if there's any doubt, the picture to your right is not a snapshot of Moustache star Vincent Lindon, who looks more like a Gallic Huey Lewis.) Also, last week's Rep and this week's Rep.