Sunday, October 29, 2006

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Apropos of Next to Nada

Because of The Brand Upon the Brain!, I guess, here's Guy Maddin's brilliant Eye Like a Strange Balloon...which is what I thought it was called. Turns out it has a far, far longer title: Odilon Redon or The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity.

Maddin operating on full cylinders. I love the shot [SPOILER!] of the old man, his eyes just stabbed through, walking through this vast, new wasteland -- one of the most eloquent and haunting images of blindness I've come across.

Of course, my real reason for posting is right here: an Editor's Pick (third down) on an all-night horror line-up from Secret Cinema, featuring a film you -- yes, you, you raging cinephile -- have never heard of; a review of Philip Noyce's moribund Catch a Fire; and, but of course, Rep.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

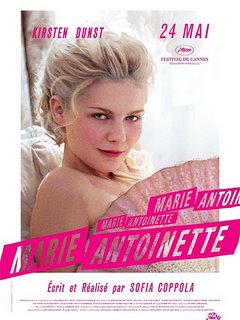

Marie Antoinette (2006, Sofia Coppola) [B+], plus two other mystery blurbs at the bottom (psst! one of them’s also a titular protag deal)

It’s all about that opening shot. M.A. has been criticized in many circles (and, in a couple cases, praised) for being overly-frivolous. In one instance, the complaint was that Sofia had the nerve to open up the film with Gang of Four’s searing “Natural’s Not In It,” thereby wrongly suggesting that a certain political exploration -- if not an actual plea for anarchism -- is on the way. Thing is, it is. Kind of. In the opening shot, Kirsten Dunst’s M.A. is seen in far shot lounging in a chair, having her shoes put on by a servant. She lazily fingers an ostentatious cake sitting conspicuously next to her. (You guessed it: I'm describing the above image!) Again, with Gang of Four blaring on the soundtrack (“The problem of leisure/What to do for pleasure/Ideal love a new purchase/A market of the senses,” etc.), Dunst sits up ever so slightly and shoots the camera an insolent, snooty look: “Fuck off, I'm the queen!”

It’s all about that opening shot. M.A. has been criticized in many circles (and, in a couple cases, praised) for being overly-frivolous. In one instance, the complaint was that Sofia had the nerve to open up the film with Gang of Four’s searing “Natural’s Not In It,” thereby wrongly suggesting that a certain political exploration -- if not an actual plea for anarchism -- is on the way. Thing is, it is. Kind of. In the opening shot, Kirsten Dunst’s M.A. is seen in far shot lounging in a chair, having her shoes put on by a servant. She lazily fingers an ostentatious cake sitting conspicuously next to her. (You guessed it: I'm describing the above image!) Again, with Gang of Four blaring on the soundtrack (“The problem of leisure/What to do for pleasure/Ideal love a new purchase/A market of the senses,” etc.), Dunst sits up ever so slightly and shoots the camera an insolent, snooty look: “Fuck off, I'm the queen!”The first problem is that some (okay, most) are confusing M.A. with S.C. Playing pop psychologist, these critics, detractors and admirers alike, think something along the lines of, “privileged daughter, raised in movie royalty, even encouraged the wrath of moviegoers back in 1990, and so forth. Why, this must be Sofia’s story! And look at how the soundtrack is littered with tracks she probably listened to back when she was Marie Antoinette’s age! QED!” This line of thinking isn’t entirely misguided. But it uses a string of director-subject links to jump to the conclusion that it’s a kind of abstract autobiography, therefore missing what the film’s really about: the point where Sofia ends and M.A. begins. The opening shot is not only a kiss-off to anyone expecting a thorough dissection of the political/social world that led to the court of M.A. and her subsequent beheading. It’s an acknowledgment that Coppola may or may not align herself with the politics of Gang of Four and their ilk. However, we definitely know that Marie Antoinette does not. To clarify, there’s no doubt that Coppola sees traces of herself in M.A. But she is not her.

The second problem is one of audience identification: how does a youngish filmmaker, who radiates a liberal-humanist vibe, justify making an even somewhat positive film about a hermetic, wasteful hedonist in this day and age? The same crisis of conscience plagued Stephen Frears’ The Queen, and it looks like both took the same path: empathize. But empathy does not require aligning one’s self with the person themselves; it simply requires seeing things from their angle. There is something noticeably punk rock -- in a topsy-turvy way, of course -- about the opening shot, signifying that she doesn’t care that you might look down upon her. But upon closer inspection, it seems that what that look is really conveying is irritation -- “Look, buddy, it’s not really my fault. I’m but a product of my environment.” And Coppola drowns us in M.A.’s own corner of this environment, a worldview simultaneously noble in it eye-rolling and decidedly less so in its disinterest in what lies just over the horizon. You can’t justify her apathy towards politics and society -- conveyed through periodic visits from an increasingly flustered/hilarious Steve Coogan -- so why bother? We know that she and Versailles didn’t give a toss about the people, and it would only look like bobbing for brownie points if she simply regurgitated the old line about M.A. and co.

The second problem is one of audience identification: how does a youngish filmmaker, who radiates a liberal-humanist vibe, justify making an even somewhat positive film about a hermetic, wasteful hedonist in this day and age? The same crisis of conscience plagued Stephen Frears’ The Queen, and it looks like both took the same path: empathize. But empathy does not require aligning one’s self with the person themselves; it simply requires seeing things from their angle. There is something noticeably punk rock -- in a topsy-turvy way, of course -- about the opening shot, signifying that she doesn’t care that you might look down upon her. But upon closer inspection, it seems that what that look is really conveying is irritation -- “Look, buddy, it’s not really my fault. I’m but a product of my environment.” And Coppola drowns us in M.A.’s own corner of this environment, a worldview simultaneously noble in it eye-rolling and decidedly less so in its disinterest in what lies just over the horizon. You can’t justify her apathy towards politics and society -- conveyed through periodic visits from an increasingly flustered/hilarious Steve Coogan -- so why bother? We know that she and Versailles didn’t give a toss about the people, and it would only look like bobbing for brownie points if she simply regurgitated the old line about M.A. and co.(Speaking of which: why all the carping about the awkwardness with which the real world infiltrates Versailles and, by effect, the last half hour of the film? It's clear that it's by design. Note that the second scene in which the American Revolution is ploddingly discussed, the scene ends with Schwartzman turning a piece of paper into a mock-telescope. Not to mention, M.A. is clearly dealing in a lack of reality: not only is this the only period piece where Aphex Twin and Siouxsie and the Banshees dominate the soundtrack, but also the only one with no unifying accents: Dunst and Schwartzman speak Yank, Coogan and Shirl Henderson do Brit, Mathieu Amalric (briefly) does French and Asia Argento does her unplaceable Euro Accent. This seemed refreshingly jarring, no less because I had just beforehand seen a movie that takes place in French but is stocked with British accents. Why do we give this shit a pass? Jesus.)

Anyway. Instead of reiterating the same-old-same-old, Coppola focuses on M.A.’s strong points: the way her visible awkwardness with functions and willingness to undercut them belies at least some care for those who serve her; her patience with Jason Schwartzman’s Louis XVI, who’s more interested in the history of locks, hunting and who possibly possesses a serious homosexual streak; the way she never actually said her famous Bartlett’s one-liner. In the second half, Coppola focuses on the way she starts coming into her own, building a life that’s both a part of and apart from Versailles: feeling free to take a lover after giving birth, asking for a looser-fit dress to wear in the garden/makeshift zoo that she’s created (not sat around and watched erected, mind), staying up to see the dawn after one of the parties. Finally, Coppola suggests that M.A. was growing, ever so generally, into a social consciousness, staying behind at Versailles as a form of suicide for previously not giving a shit. Coppola acknowledges that all this doesn’t excuse M.A., but it does at least partially explain her.

Anyway. Instead of reiterating the same-old-same-old, Coppola focuses on M.A.’s strong points: the way her visible awkwardness with functions and willingness to undercut them belies at least some care for those who serve her; her patience with Jason Schwartzman’s Louis XVI, who’s more interested in the history of locks, hunting and who possibly possesses a serious homosexual streak; the way she never actually said her famous Bartlett’s one-liner. In the second half, Coppola focuses on the way she starts coming into her own, building a life that’s both a part of and apart from Versailles: feeling free to take a lover after giving birth, asking for a looser-fit dress to wear in the garden/makeshift zoo that she’s created (not sat around and watched erected, mind), staying up to see the dawn after one of the parties. Finally, Coppola suggests that M.A. was growing, ever so generally, into a social consciousness, staying behind at Versailles as a form of suicide for previously not giving a shit. Coppola acknowledges that all this doesn’t excuse M.A., but it does at least partially explain her.Also, this movie needs to start making some serious money, no less because it’s the first time I’ve really felt that Sofia Coppola has earned her acclaim. So, this is a note to the pervy teenager crowd, should they accidentally Google their way here: it’s PG-13 and a couple scenes put Spider-Man’s upside-down rain kiss to shame. What are you waiting for, pervs.

Edmond (2006, Stuart Gordon) [B]

Or, David Mamet’s contribution to the Chappelle’s Show’s feature, “When Keeping it Real Goes Wrong.” Of course, that’s if you think William H. Macy’s white-collar schnook even goes wrong, when it’s entirely possible to read it as him going, um, good -- discovering a sense of purpose and even landing an apparently healthy relationship. (At least -- SPOILER ALERT IN SECTION G! -- he can chat with prison bitchee Bookem Woodbine.) I think it’s the latter. Under all the race-baiting, all the seediness, all the bluntly shocking moments, there’s a certain unmistakable empathy in Mamet’s dark-night-of-the-soul trip. On the one hand, you have 23 short scenes where Macy’s Edmond is either rebuffed for sex (because of money, specifically lack thereof) or triumphant, but only when he acts on his burgeoning racist and homicidal tendencies. Very shocking, especially when you throw Denise Richards in there doing MametSpeak™. On the other, you have an apparently asexual man taking a journey of the self, hacking his way through a slew of wobbly facades before arriving at this: that he fits in best in prison and as a homosexual. Gordon may capture the sleaze of its New York (actually, L.A.) setting, but the humanity is not lost on him, despite (or because of) the rigidness of the text. At least in the movie version, the most shocking thing about Edmond is its entirely earnest suggestion that becoming a prison bitch could actually be enlightening.

Little Monsters (1989, Richard Greenberg) [D-]

I have no excuses for why I watched this, a nugget from my ten year old self. I can’t even claim morbid curiosity, because I knew it would do the opposite of holding up. It’s possible I’m a masochist. In any case, the only fascinating thing -- apart from the meta- delight of seeing Fred Savage and Daniel Stern, two Kevin Arnolds, playing father and son -- is the beneath-cheap, Forbidden Zone-esque design of the sub-world, where dwells the host of aesthetically-inconsistent monsters (pumpkins! blue people! big fat guys with hunchbacks and shit). Also, it is beyond painful to watch even as unfunny a comedian as Howie Mandell literally thrown in front of the camera and told to simply “free associate!” Only Funny Games 2007 should provide a more unnerving experience in audience-complicity. I mean, that dude’s got nothin’...

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Sorry.

Reviews of Clint's Flags of Our Fathers and Zhang's Riding Alone For Thousands of Miles, plus Rep, in this week's PW.

Probably returning to semi-regular blogging duties sometime this week. Newsflash: The Prestige is fawesome.

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Three Weeks of Me

Seems I've been neglecting to link to my junk. Reviews: The Last King of Scotland (at bottom), The Queen (at top), and Jesus Camp (third down). A-lists/Editor's Picks: Secret Cinema's ransacking of their archives and I-House's "Views of a Changing World" series (at bottom). Reps: here, here*, and here.

*This one is where you can find words on the films in I-House's aforementioned "Views of a Changing World" series. Among these titles: Excellent Cadavers, Workingman's Death, and two by Chris Marker, including his latest, The Case of the Grinning Cat. Pretty kickass series, if you ask moi.